Prospect Research

Walking the Line with Prospect Vetting: Just How Much Diligence Is Due?

By Lindsey Nadeau | August 08, 2019

More than ever, the world is paying attention to who is funding nonprofits. From François Pinault’s controversial pledge of $113M for the restoration of the Notre Dame Cathedral in France to the boycott of Sackler family gifts in the U.S., the motives of donors and the policies (or lack thereof) of institutions are coming under fire in the media. An organization’s reputation is on the line every time it accepts or rejects a gift from a donor. This issue is multi-faceted, as donors also make headlines by revoking gifts from nonprofits allegedly not meeting donors’ expectations and as nonprofits return gifts to donors to preserve the organization’s integrity.

These trends beg the question: What role do prospect development professionals play in protecting their organization from controversy? In the last 10 years, I have received a growing number of vetting requests. When speaking with gift officers about their desire to vet a prospect, it was clear they were concerned about headlines like the ones above. However, even after having explored this topic deeply by writing an Association of Advancement Services’ (AASP) Best Practice in Vetting Prospects (see below for how to access via Apra’s website), I still find myself grappling with prospect development’s role in this process. Over the course of my career, fundraising leadership has asked to expand the vetting scope of nearly every prospect development shop in which I have worked, and these conversations are challenging for many reasons.

At the outset, prospect development’s ability to vet a prospect appropriately and thoroughly depends on an organization’s ethical standards. Some organizations have very clear ethics policies. I once worked at a nonprofit that did not accept corporate or government funding in order to preserve its independence. As a cause-based organization that was fighting the influence of money in politics, it was imperative to walk the talk. In higher education, shops often have a standard gift acceptance policy grounded in the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) guidelines, but not a written policy about the ethical standards of its donors. How would an organization begin to outline appropriate ethical standards? And without articulated standards, on what is prospect development basing its vetting recommendation?

An organization’s reputation is on the line every time it accepts or rejects a gift from a donor.

In addition, even when vetting research recommends halting a solicitation or declining a gift, organizational leadership sometimes proceeds nonetheless. What influence does vetting research actually wield? Vetted prospects decline solicitations, and gift officers may halt a vetted prospect’s planned solicitation for strategic reasons separate from reputational risk. How else might prospect development have invested its time to move the fundraising enterprise forward? In my experience, requestors rarely seem surprised by the risks identified in vetting research. So, why are we vetting that prospect? In our increasingly ROI- and analytics-driven profession, how do we quantify both the value and opportunity cost of this resource-intensive work?

Vetting can also become a battleground of scope creep. One of my senior leaders once said they believed prospect development should vet every principal prospect in the proposal pipeline. I was befuddled imagining how that might be feasible. At what point in the cultivation cycle do you vet a prospect? If vetting occurs “too soon,” and the solicitation takes three years to close, does the prospect need to be vetted again? Furthermore, do you vet donors as well as prospects? What if a longtime donor is interested in a highly visible naming opportunity? Do you vet them even though your organization has already accepted gifts from this donor in the past? What if a longtime donor’s gift would establish a new, potentially controversial program? Did your scope just expand to vet gift-specific solicitations? What if a prospect funds a cause at another nonprofit that conflicts with your organization’s mission? If a prospect is publicly associated with a marquee nonprofit, do you really need to vet the prospect? Instead, do you vet the nonprofit with which the prospect is associated?

With limited guidance on the ethical standards upon which vetting is based, questionable influence on final outcomes and the inability to predict a prospect’s future reputational risk, determining your prospect development team’s role in the vetting process and establishing a written policy can seem hopeless and painstaking. Yet, while these are difficult conversations to have, they are important and necessary.

In my experience, anyone asking about your vetting practice is as passionate as prospect development professionals about protecting your organization, so remember to assume good intent. Everyone’s perspective on your current practice will be uniquely informed by his or her role. Non-prospect development staff may be unaware of the significant time and skill required to vet a prospect appropriately, so educate your colleagues and leadership as you go. Take steps toward routinizing this process, and where possible, convene a task force of key stakeholders (including leadership!) to determine which prospects to vet when and whether or not to pursue the solicitation. The questions outlined above have no definitively “right” answers. Revisiting these circular debates may give you a headache, but when you begin the dialogue, you are taking a purposeful step in the right direction.

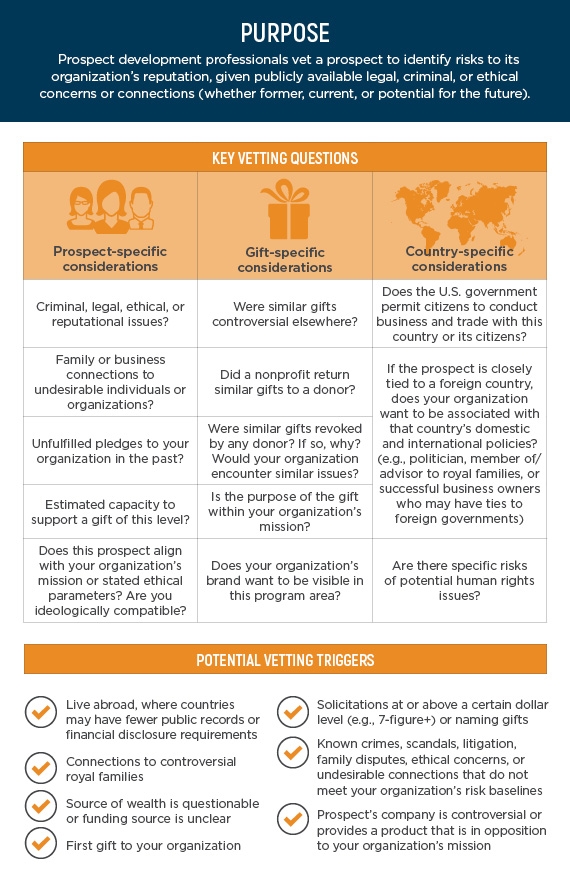

New to vetting research? The below infographic summarizes vetting research fundamentals, and be sure to check out the full Association of Advancement Services’ (aasp) Best Practice in Vetting Prospects. The Best Practice details key considerations in creating a vetting policy, process mechanics and sample resources. Not an aasp member? Apra members have access to aasp Best Practices through Apra’s partnership with aasp! Follow this link, and select “Apra members Access to aasp Best Practices.” Login, check out, and then download the file.

Lindsey Nadeau

Managing Director of Prospect Development & Campaign Planning, UNICEF USA

Lindsey Nadeau is the managing director of prospect development and campaign planning at UNICEF USA, where she guides the organization toward data-driven decision making and automation. She was previously the director of research and relationship management at The George Washington University, led development operations at the Center for American Progress, was an assistant director of prospect research and management at American University, and held multiple roles (read: too many hats!) in development operations at Public Citizen. She holds a bachelor's degree in economics from American University.

Lindsey is a member of Apra International’s board of directors, a former president of Apra Metro DC, chaired Apra International's Conference Planning Committee, and served on Apra International’s Nominations, Editorial Advisory, Data Analytics Symposium, Apra Talks, and Body of Knowledge committees. She has served as co-chair and faculty for CASE's annual Prospect Development Conference and is a former chair of the aasp Prospect Development Best Practices Committee. She is an instructor at Rice University's Center for Philanthropy & Nonprofit Leadership, teaching “Relationship Management: Data, Policy, & Insight” and serves on iWave’s Advisory Counsel.