Relationship Management · Prospect Engagement

Community Ties: A Strategic Approach to Relationship Mapping

By Kristal Enter | January 12, 2024

Editor's Note: This article is featured in Best of Connections 2024. Read the editor's message from Apra Content Development Committee Co-Chairs Jennifer Moody and Jennifer Huebner to learn more about the top articles of the year.

Editor's Note: This article is featured in Best of Connections 2024. Read the editor's message from Apra Content Development Committee Co-Chairs Jennifer Moody and Jennifer Huebner to learn more about the top articles of the year.

Most prospect researchers can readily recount their most successful finds — the ones that took every ounce of investigative skill and creative thinking — that make up the art and science of prospect research. I recall one find that was particularly impactful on my practice. A gift officer was searching for a way to engage a cold prospect, and after sifting through the prospect’s board memberships and professional affiliations, there was little to help us connect with this person. However, I struck gold when I came across a document on a town website, noting the prospect had been a coach of his child’s youth soccer team with one of our organization’s most important connectors. This connection had not been (and would not be) documented in any financial filings or relationship mapping databases.

Uncovering a New Approach to Relationship Mapping

This find led to me to think more deeply about how we research relationships and how the concept of community intersects with our work. The field of fundraising has historically celebrated, elevated and glorified individual philanthropists (and perhaps sometimes their immediate family). Through the way we conduct research and report out information, the prospect research profession has contributed to this focus.

The question of who someone knows boils down to what roles, positions or titles the individual holds and how we might be connected through those. Relationship mapping has often meant examining corporate or nonprofit board memberships and documenting potential connections through them. We can reimagine this — especially in the larger context we find ourselves in, when we are all rebuilding (and potentially rethinking) our sense of community in our personal and professional lives after literal years of isolation.

Revisiting Community as the Basis for Connection

To start, we can turn to thought leaders who have considered the relationship of the individual to the formation of communities. As pathfinder, writer and facilitator Mia Birdsong notes in her book “How We Show Up: Reclaiming Family, Friendship, and Community:” “We exist, not as wholly singular, autonomous beings, nor completely merged, but in a fluctuating space in between.”

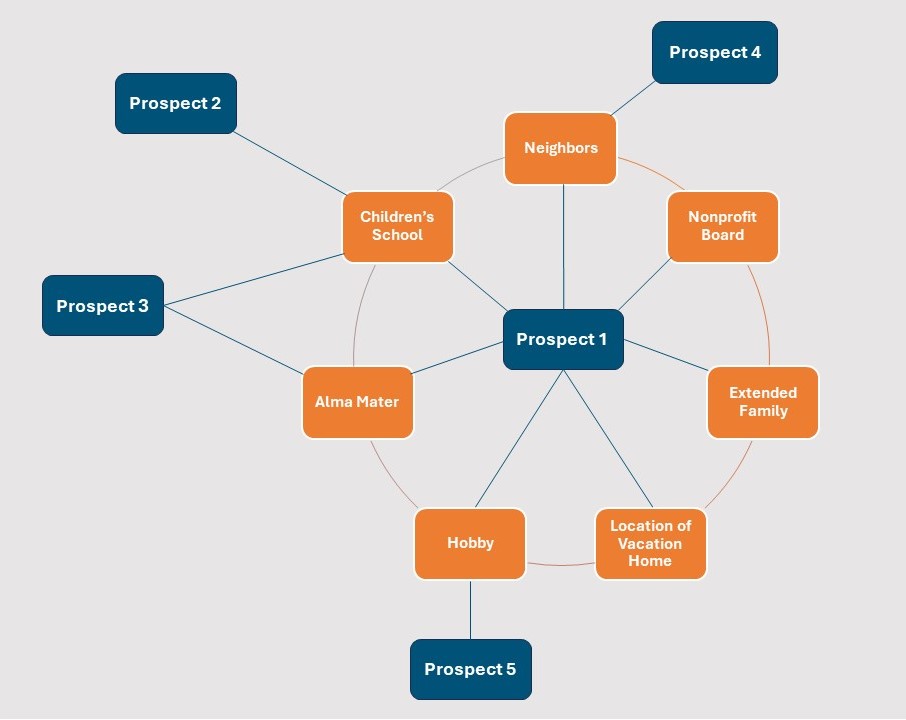

Relationship mapping starts to look very different if we as prospect development professionals apply what Birdsong suggests about community: each prospect is not an island, but instead an individual member of a kaleidoscope of larger communities and networks. These communities are where we find the invisible threads that keep us as human beings intertwined. This might be through formal board service, but it is also far more expansive. Someone’s important communities may include family (immediate, extended or chosen), location (neighborhood or town), work, school, religious, social, civic, philanthropic or recreational spaces.

Communities are not static. Prentis Hemphill, cofounder of the Groundwork Project and founder of the Black Embodiment Initiative, discusses this with Birdsong on their podcast “Finding Our Way:” “Maybe community is like a body. Community feels and responds. It lives, it grows, it changes.” Communities may ebb and flow over time; the kind of community support important to a young professional is not the same as what might be to empty nesters.

This mindset is especially critical as we seek to build more inclusive philanthropic communities around our organizations by intentionally engaging a diverse range of people, rather than the most pursued prospects who typically identify as older, white men. At its very core, fundraising is community building. We invite those who care about the organization to give. The act of giving to an institution is a way of engaging in a community and being part of something larger than an individual.

Most organizations have genuinely good intentions to work toward creating a philanthropic community where our donors feel like they belong. But if we are identifying, researching, cultivating and stewarding our donors simply as individuals — and not as members of richly complex communities and networks — how can we truly achieve the goal of building community around our own organization?

Applying the Basics To Reexamine Our Practice

How do we operationalize this? Every prospect researcher can take one important step: examine how you view community (professionally and personally) and how that might impact your work. Ask yourself the following:

- What are your thoughts on the Birdsong and Hemphill quotes above?

- What is community to you?

- What communities do you feel included in?

- How has community changed over time for you?

Prospect researchers are the tellers of stories on individuals, and it is our responsibility to understand how our own narratives and life experiences impact the way we tell stories about other people.

The most important questions a frontline fundraiser could ask a prospect or donor are: “What kinds of communities do you identify as being part of?” and “What makes you feel as though you are part of those communities?” These questions can yield powerful insights on individuals and what makes them feel included.

Prospect researchers can also reframe their research practices to make a subtle shift toward prioritizing researching the communal with the goal of better understanding the individual. We must keep in mind that sometimes communities emerge from sensitive or difficult circumstances. As such, we must adhere to the ethical standards of our industry. This includes taking care in how we report and store information and ensuring we keep our relationship mapping research in the realm of self-disclosed or publicly available information.

But, in the example of the soccer coach, what would have happened if I started my line of inquiry with considering communities the prospect might be part of: the town they live in, their neighbors and whether they had children? Although frontline fundraisers may not articulate it, when they request relationship mapping from prospect research, they may actually be asking for this kind of rich information.

Instead of providing the gift officer something like this:

It might look something more like this:

Finally, we can also reexamine our research products to explore whether there might be opportunities to elevate the notion of community, rather than focusing on the individual. For example, are there research products available to document family members who have multiple generations involved in philanthropy? While many shops likely have products for corporate or foundation donors, are there research products available for instances of when many individuals pool their money to make a philanthropic gift, such as through giving circles, churches or unions?

This may feel a little speculative or uncomfortable to prospect researchers used to dealing in the hard data. And it is asking more of the researcher — to think more creatively, investigate more paths of connection and document more information. But if prospect researchers can lean more into the art of relationship mapping, rather than the science, we might just turn up more connections.

Author’s note: A big thank you to Denise Harris, Ina Drouin, Jolene Crosby-Jones and Mike McNally for their partnership in developing this article.

Kristal Enter

Associate Director of Prospect Research and Management, Massachusetts General Hospital

Kristal Enter has held prospect research and prospect management roles at Massachusetts General Hospital since 2018. Prior to joining MGH, she was a senior research analyst at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Enter has worked in the fundraising field since 2013 and previously held roles at Partners In Health and University of Massachusetts Boston. Her graduate school work at the University of Cambridge focused on the integration of higher education in the American South.