Prospect Research · Additional Keywords · Grateful Patient · Content Type · Article · Industry · Health Care

Patients and Fundraising: All for the Social Good

By Andillon Hackney | May 31, 2019

The Grateful Patient Fundraising conversation is very cyclical in our profession, and right now with an international spotlight on privacy, we are re-examining the ethics and myths at the intersection of patients and fundraising. As a prospect development professional, and not a compliance expert, here are some ethical considerations that continue to bubble up.

The term ‘Grateful Patient Fundraising,’ as described by an Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) abstract, “encompasses activities aimed at encouraging and supporting patients’ philanthropy to health care institutions. These activities are grounded in mutual goals of bringing about a social good.”1 Patient fundraising, like all philanthropic programs whether with alumni or members, has constituents who become part of a network that supports the non-profit organization. The only difference here is the added layer of patient privacy, and it is no small layer. Let’s examine the popular myths that resurface and reignite the ethics conversation.

Myth 1 – Grateful Patient Fundraising is new!

Not so. In the early 20th century, John and Charlotte Astor and John D. Rockefeller Jr. funded a hospital that would later be renamed Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center because both families had personal experiences with cancer that motivated them to give. Here are some other institutions who benefitted from grateful patient philanthropy: Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Center. These are just a few examples of the long trajectory of health care philanthropy.

Myth 2 – Wealth Screening Patients is ‘Unseemly.’ 2

A recent New York Times article quoted bioethicist Arthur Caplan from the NYU School of Medicine who succinctly defined the problem: “These various tactics, part of a strategy known as ‘grateful patient programs,’ make some people uncomfortable. Wealth screenings strike me as unseemly but not illegal or unethical.” The word “tactics” definitely sets a battle tone, and certainly not a very positive one. And I think that tone comes from not seeing the whole landscape of regulations versus hospital revenues.

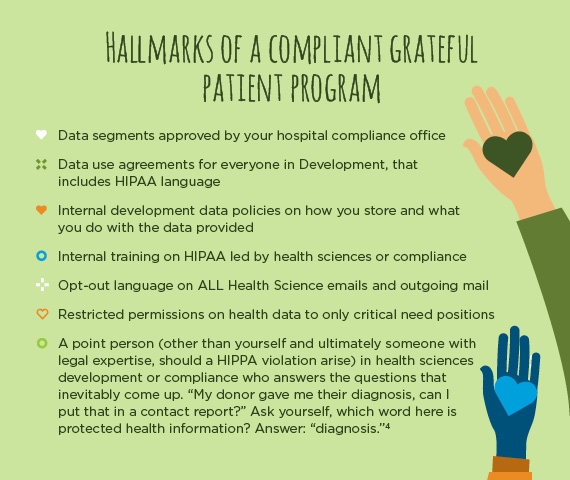

When HIPAA regulations were amended in 2013, it was not illegal or unethical for health care institutions to use demographic patient data for fundraising purposes, including screening and marketing. HIPAA mandates opt-out policies that ensures privacy for patient protection. HIPAA compliant data sets do not include diagnosis or outcomes either, and I think that’s where “unseemly” is misunderstood by most. The data segments for patients look exactly like any other demographic data set: name, address, date of birth, phone, gender, date of service, provider (potentially) and general department.

An untold part of this dynamic is that, concurrent to initial HIPAA regulations (1997), The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 sent institutions into the red by reducing rates of reimbursements and revenue.3 If hospitals have a decrease in insurance reimbursements and/or a safety net hospital taking in a large percentage of uninsured patients, having philanthropy shoulder some of the revenue helps keep the doors open. The result is that instead of waiting for the next Astor or Rockefeller to donate, hospitals have become proactive in investing in fundraising—screening being only one small piece of that investment.

Myth 3 – Physicians asking for donations would create dilemmas for those patients in need of their services.

The underlying concern from both physicians and patients is that a patient might think that if they don’t “give” they won’t receive good care. The examples that are used in the NYT article referenced earlier, all seem to revolve around grateful patient direct mail solicitations, rather than a deviation from a physician’s Hippocratic Oath. Though not unethical or illegal, there are probably instances where tact and judgement took a back seat to a zealous direct mail campaign. One way to avoid these instances is annual development and physician trainings that emphasize that grateful patient fundraising is not a donation for care transaction. Physicians and nurses are really partners with fundraising in identifying potential, either by spotting wealth indicators or a patient’s passion for research, or interest in giving back.

Myth 4 – The Grateful Patient population is an untapped prospect pool.

Newly screened patients are going to uncover so much hidden potential, right? Well, unless you have absolutely no donors, odds are that some of your best donors are also current patients. After many screenings—daily, weekly, monthly—it is unsurprising that after all that work the top prospects list often resembles the top donors lists. That is not to say, there aren’t new prospects, it just means we as prospect development professionals must learn to manage expectations. New prospects come to us only two ways: screenings and referrals, a narrower stream than, say, a university alumni pool.

Myth 5 – There is a patented Grateful Patient Program.

In fundraising shops and at conferences we talk about the Grateful Patient Program, but have you ever noticed there is no one way of doing things, no spot on perfect “program?” The reasons could be because every organization is unique, but I think the problem may be in semantics of the word “program.” The best patient fundraising seems to be just that: relationship building with patients and physicians addressing a particular need. Here are some real examples of what I consider grateful patient fundraising:

- During the recession, when insurance reimbursements were lagging, a star neurosurgeon supplemented $80K a month out of his pocket to cover salaries for his neuro team. The stakes were life and death access to care. Result: a grateful patient stepped up to endow fellowships for the neuro team.

- A philanthropist whose friend has a neuro-degenerative disease wants to accelerate stem cell research from lab to bed, in order to help his friend. The resulting gift created a collaborative world-class center accelerating research and saving lives.

- A widow who struggled with inadequate palliative care for her husband decides after his death to donate toward a better and more compassionate palliative care program to the same hospital where he was treated.

In each case, the underlying motivator was the donor/patient’s desire to make things better. These inspiring stories are what seem to get lost in the ethics around patient fundraising. I think we also forget that HIPAA regulations do a fantastic job of protecting patient data, while also leaving room for philanthropy to enhance the progress of health care.

In conclusion, the ethical debate around patient fundraising will resurface again and again, so, let’s not lose sight of the social good philanthropic patients and donors do. That’s the “why” to “why have a grateful patient program” at all.

Sources:

1. Academic Medicine, Nov. 2018 from the Association of American Medical Colleges Abstract: Ethical Issues and Recommendations in Grateful Patient Fundraising and Philanthropy

2. New York Times Article: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/24/business/hospitals-asking-patients-donate-money.html

3. National Center for Biotechnology Information: The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act: is it really all that bad? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1305898/#sec1_4title

4. What is PHI? https://www.hipaajournal.com/what-is-considered-protected-health-information-under-hipaa/